- High and persistent inflation in 2022 has led to a major shift in the monetary policy decisions of the main central banks and a deterioration in financing conditions

- The tightening of monetary policy is leading to sharp upturns in global sovereign debt yields

- This deterioration in financing conditions will eventually be transferred, albeit gradually, to the deficit and debt

- The debt ratio has recorded four consecutive quarters of falls and stood at 117.7% of GDP in the first quarter of 2022

- In absolute terms, debt has continued to grow and reached a new all-time high of €1.45bn

- Under AIReF’s forecasts, debt is projected to fall by 9.6 points over the next four years to 108.8% in 2025

- Beyond the reduction that is expected in the short term, once the boost to growth ends, debt will resume an upward path under the assumption of a no-policy-change scenario

- The simulations show that a structural primary deficit of between 1.5% and 2.5% of GDP from 2025 would place the debt ratio between 125% and 140% of GDP in 2040

The Independent Authority for Fiscal Responsibility (AIReF) has published the update of the Public Debt Monitor following the tightening of monetary policy, in which it reviews the major shift in the tone of the decisions of the main central banks around the world and its consequences for financing conditions and debt sustainability.

AIReF notes that the economic recovery after the health crisis led to an initial increase in inflation related to bottlenecks in global logistics and shortages of supplies at a time of strong demand. At that time, the upturn in inflation was considered to be of a temporary nature. Factors such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine have driven up the already high price of energy, and deepened and accelerated the increase in prices across the world, raising inflation to record levels. Central banks around the world have been reacting, to a greater or lesser extent, by tightening monetary policy in response to this inflation, which is now considered to be less transitory, although medium-term inflation expectations continue to be anchored at contained values. Specifically, more than 60 central banks, according to Bloomberg’s calculations, have already raised rates this year.

Against this backdrop, AIReF reviews in the Monitor the decisions taken by the European Central Bank (ECB), the United States Federal Reserve (Fed) and the Bank of England (BoE). With these movements, central banks aim to reduce lending, lower asset prices and cool down the economy (without plunging it into a recession) so that inflation will return to its path in a “soft-landing” scenario.

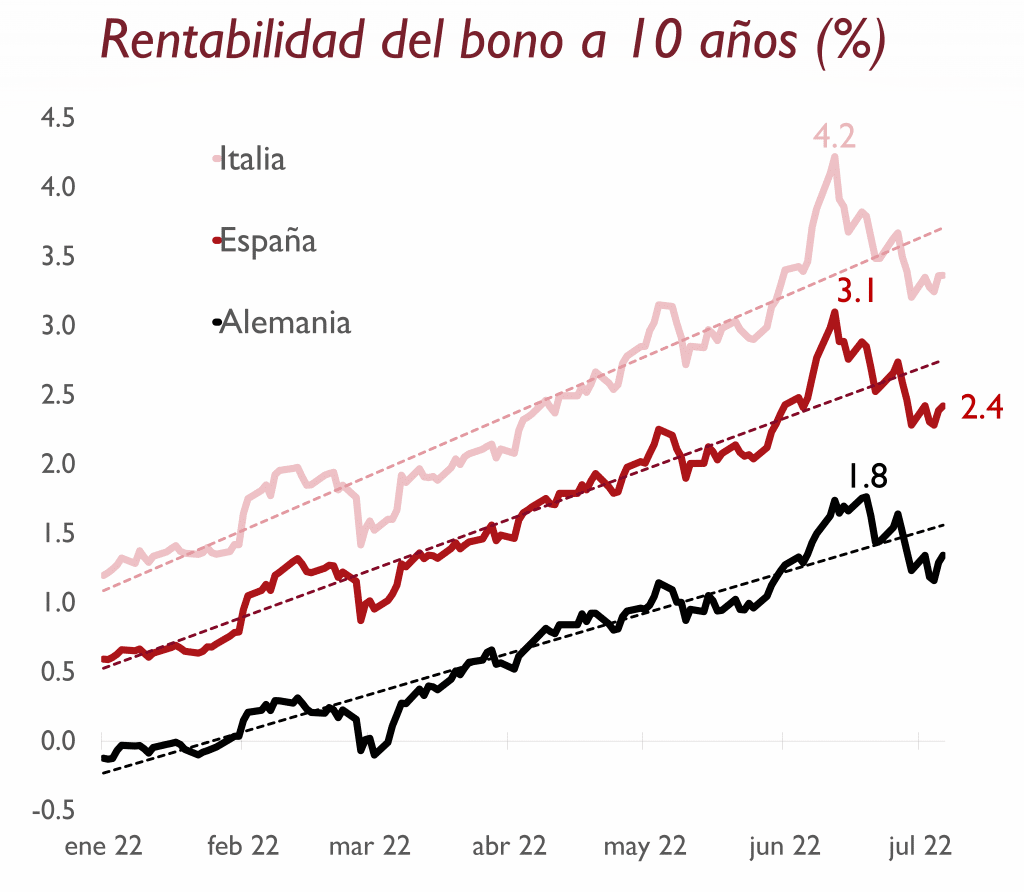

According to AIReF, this tightening of monetary policy is leading to sharp upturns in global sovereign debt yields, with a trend that has accelerated over the year as inflation has continued to record unexpected increases. The yield on the ten-year bond has risen by 180 basis points and exceeded 250 on June 14th, values that have not been seen since 2014.

The scenario of major uncertainty that has arisen in 2022, with background trends that have worsened following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, is triggering sharp movements and overreactions in financial markets. In recent months, there has been a sharp increase in the volatility of sovereign bond yields and an upward trend in risk premiums, exacerbated by the announcement of the end of asset purchase programmes. In the case of Spain, the spread on the ten-year bond against the German bond has risen by 37 basis points so far this year.

With regard to the fiscal implications, the deterioration in financing conditions will eventually be transferred, albeit gradually, to the deficit and debt. The tightening of monetary policy in response to persistent inflation is having a major impact on sovereign debt yields, which will result in a higher financial burden. Higher financing rates impact the new debt issues, and will be gradually transferred (given the high average maturity) to the average rate of the portfolio. Compared with the SPU scenario, an increase in the average issuance rate of 100 bps in line with recent developments would raise the implicit rate forecast by 0.3 points (up to 2.2% in 2025), the financial burden by 0.4 points of GDP (up to 2.4%), and the debt ratio by 0.7 points.

The end of the ECB’s purchase programmes (PSPP and PEPP) and the future, albeit distant, reduction of sovereign debt on the central bank’s balance sheet, pose a significant challenge to the yield on Spanish debt, as it requires the return of a large part of the investor base (mainly the resident base) that has been displaced in recent years.

Evolution of the debt

AIReF’s projections paint an unfavourable trend in the medium- and long-term debt ratio under a no-policy-change scenario. The debt ratio has recorded four consecutive quarters of falls and stood at 117.7% of GDP in the first quarter of 2022. The cumulative reduction in the last year is 7.5 points, of which 0.7 points have been recorded in the last quarter. This significant reduction is mainly due to the denominator effect, given the strong upturn in economic activity and prices. In absolute terms, public debt has continued to grow, adding €26.62bn to reach a new all-time high of €1.45tn.

Compared with the level prior to the pandemic, the debt ratio has risen by 19.4 points. GDP, the denominator of the ratio, has already stopped contributing negatively to the increase resulting from the pandemic, with the public deficit causing almost all the change. At a sub-sector level, the largest increase in the debt ratio has taken place in the Central Government and the Social Security Funds. The debt ratio of the LGs has remained stable, while that of the ARs has recorded a slight increase.

Under the macro-fiscal forecasts prepared by AIReF to assess the Stability Programme, the debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to fall by 9.6 points over the next four years to 108.8% in 2025. Most of the reduction in the debt ratio (7.2 out of the 9.6 points forecast up to 2025) takes place in the first two years, coinciding with the economy’s sharp nominal growth, while it is forecast to stabilise somewhat as from the third year. The government deficit will continue to contribute significantly to the increase in debt, with a financial burden that will rise in absolute terms, but will remain stable relative to GDP due to the sharp increase in nominal GDP.

Beyond the reduction in the debt ratio that is expected in the short term, once the boost to growth as a result of the rebound in activity following the shutdown during the pandemic ends, AIReF estimates that the debt-to-GDP ratio will resume an upward path under the assumption of a no-policy-change scenario. The simulations performed by AIReF show that a structural primary deficit of between 1.5% and 2.5% of GDP from 2025 (in line with the latest estimates by the Government and AIReF, respectively) would place the debt ratio between 125% and 140% of GDP in 2040.

Expectations of higher interest rates exacerbate debt dynamics, according to AIReF. Thus, higher interest rates will generate a greater financial burden, which if not offset with some adjustment, will end up having an impact on the debt ratio. The simulations show that a financial burden between 1.3 and 1.8 points higher (depending on the scenario of the evolution of the primary balance) results in an increase in the debt ratio of between 12 and 16 points in 2040.